ANALYSIS: Why Nigeria’s move to raise academic qualifications of its leaders should be welcomed

By Haleem Olatunji

In October 2018, former emir of Kano, HRH Muhammadu Sanusi, raised an alarm over the crop of leaders who have governed and those governing Nigeria, a country famously described as the “Giant of Africa”.

Speaking at the 9th convocation ceremony of Nile Abuja, where he was conferred an honorary degree of Science alongside the the Alaafin of Oyo, Oba Lamidi Adeyemi III, Sanusi said Nigerians have chosen to elect uneducated leaders across the different levels of government.

“We have to take an interest in the quality of our leaders and representatives, in the level of education. If you look around this country, at many levels of leadership, we have elected and we have chosen to elect people who do not have an education. And because they are not educated, they cannot give education,” Sanusi, a former Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) governor, had said.

This statement from the former emir, famous for his advocacy on education, can be linked to the latin maxim, nemo dat quod non habet, which literally means no one can give what they do not have.

Sadly, Nigeria’s 1999 constitution (as amended) stipulates that an individual is qualified for the office of the president or governor if such candidate is educated “up to at least school certificate level or its equivalent”. This portion of the constitution has been criticised on several grounds, including the promotion of mediocrity in governance.

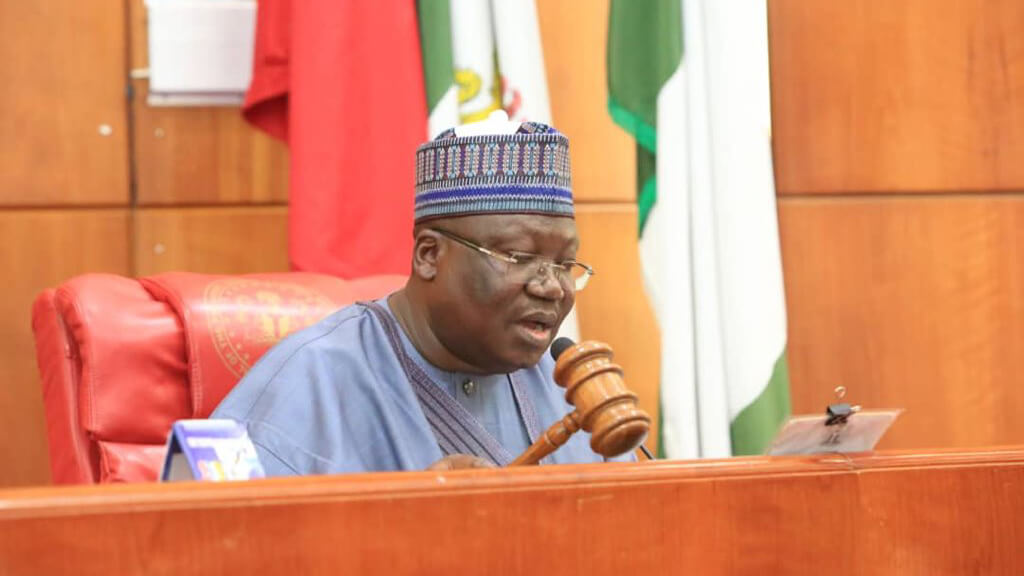

Perhaps, it is due to public outcry for a better crop of leaders that Senator Gyang Istifanus, representing Plateau north, sponsored the constitution amendment bill to fill the gap.

EXISTING ACADEMIC CRITERIA Vs EXPECTATIONS FROM CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT BILL

In the current constitutional framework, section 131 (d) of the 1999 constitution (as amended) provides that a person shall be qualified for election to the office of president if- (d) “he has been educated up to at least school certificate level or itsequivalent.”

Section 177 (d) of the same constitution stipulates that candidates contesting election into the office of state governor must have been educated up to at least school certificate level or its equivalent. By virtue of section 142 (2) and 187 (2) the provisions on educational qualification of president and state governors apply to vice president and deputy governors respectively.

Sections 65 (2) (a) and 106 (c) of the constitution prescribes that candidates contesting elections as national assembly and state house of assembly members respectively must also have been educated to at least school certificate level.

Meanwhile, the constitutional amendment bill, which has since passed second reading at the senate, seeks to raise the academic qualification for election into the office of president or governor.

The bill is seeking to amend the constitution to make the minimum academic qualification for president a higher national diploma (HND) or its equivalent and that of governor and members of the national assembly a national diploma or its equivalent.

It also seeks to provide for education up to the national diploma level as the minimum qualification for house of assembly members. But the question is to what extent will this bill, if approved, impact Nigeria’s political sphere?

BUHARI AND HIS EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION CONTROVERSIES

Ahead of the 2015 and 2019 elections, one major topic which dominated media conversations and political debates was the qualification of President Muhammadu Buhari to contest both elections. After he defeated former President Goodluck Jonathan, a doctorate degree holder, in 2015, Buhari sought re-election in 2019, where he contested and won against Atiku Abubakar, candidate of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP).

In a 43-page petition filed at the election tribunal, Atiku and the PDP had challenged Buhari’s emergence as winner of the election and considered “irrelevant”, claims that he attended a secondary school.

“That is all irrelevant to his inability to produce his primary school certificate, secondary school certificate or WASC and his officer cadet qualification, whatever that means. officer cadet is not a qualification or certificate under the constitution and electoral act; nor is it known to any law,” the petition read.

The petitioners had also argued that what is contained in the Cambridge University WASC certificate tendered by Buhari before the tribunal is different from that issued by the Provincial Secondary School, Katsina.

During cross-examination at the trubunal, a former official of the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), Oshideinde Adewunmi, said the president obtained a Cambridge University West African Examination certificate, but explained that the certificate presented to the tribunal has a typographical error.

He said that the Cambridge certificate has “Mohamed Buhari” rather than “Muhammadu Buhari” as the name of the president bears. Adewunmi also said though the Cambridge certificate has six subjects, but the president sat for eight in 1961.

HOPE FOR POLITICIANS

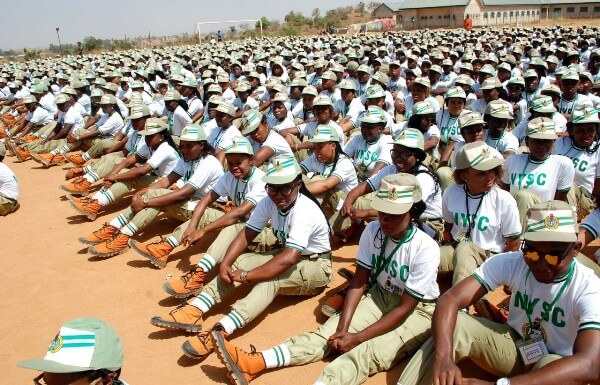

Like Buhari, there are several Nigerian politicians enmeshed in academic qualifications controversies ranging from WAEC results to certificates obtained from the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC).

The case of a former minister of finance, Kemi Adeosun, comes to mind, as well as the sack of the All Progressives Congress (APC) candidate, David Lyon, by the Supreme Court less than 24 hours before his inauguration as governor of Bayelsa state.

The decision of the apex court was in affirmation of the verdict of a federal high court disqualifying Lyon’s running mate, Biobarakuma Degi-Eremienyo, for submitting forged credentials to INEC.

In October 2015, the Yobe legislative elections petitions tribunal also nullified the election of the lawmaker representing Nangere/Potiskum constituency in the house of representatives, Sabo Garba, for lack of educational qualification.

All these are cases showing how Nigerian politicians scale the fence just to stage qualifications for political offices. With an increase in the educational qualification, it is most likely that such educational qualification will either become a thing for sale in academic institutions or a credential that will be forged by desperate candidates.

DOES EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION INFLUENCE ELECTORATES DECISION?

In Nigeria, winning election is never determined by the educational qualification of a candidate. Using the two previous presidential elections as case studies, in 2015, Jonathan, a master’s and doctorate holder from an existing federal university lost against Buhari, whose secondary school level qualification was debated in court and across various platforms.

In 2019, Buhari also defeated educated personalities such as Kingsley Moghalu, a Nigerian political economist, lawyer, and professor in International Business and public policy at the Tufts University Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, as well as Fela Durotoye, a business consultant, leadership expert, motivational speaker, and graduate of Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU).

While Buhari got over 15 million votes, Moghalu and Durotoye had 21,886 and 16,779 votes respectively. It was indeed a landslide victory against them.

As a result of poverty, Nigerians are more influenced by fleeting materials in form of little cash, household items, among others. Degree of intellectual capacity, knowledge of good governance and expertise in administration doesn’t come to mind when franchise is often exercised by most electorates.

If only those who appreciate education are elected into position, many of Nigeria’s problems would have been solved. But as the senate seeks to increase the educational qualification, it is hoped that those who emerge subsequently are crop of leaders who know and appreciate the value of education and whose actions in government will speak volume of such value.

Like Sanusi said at the convocation ceremony, “we need to lay more emphasis on the quality of people we elect to executive and legislative offices and we need to make sure that those to whom we entrust policy are themselves educated and know the value of education.”