Personalisation of Nigerian institutions and the hiatus in fight against corruption

By Chimaobi Afiauwa

When former Barack Obama first came to Sub-Saharan Africa after his historic election as US President, he made a very profound statement to African leaders. Addressing the Ghanian Parliament at the Accra International Conference Centre in 2009, the first American President of African descent said: “Africa does not need strongmen, it needs strong institutions”.

Coming from a country where institutions have been built to optimally function without excessive interference of the strongmen, Obama knew the importance of strong institutions in driving government policies. This, perhaps, was what President Muhammadu Buhari and his political allies did not understand back in 2015 when they promised to fight corruption in Nigeria

If there was anything that made the candidacy of Gen. Muhammadu Buhari (retd.) and his political party, the All Progressives Congress (APC) to be very popular in the 2015 Presidential election, it was the promise to fight corruption. His campaign managers and supporters had portrayed him as the puritanical General who has the moral perpendicularity and impeccability to zap corruption in Nigeria.

Hopes were high amongst many Nigerians that, at least, for the first time, the insanity of corruption was going to be sanitised by the ‘no nonsense’ General. Buhari’s track record of War Against Indiscipline (WAI), of course, gave credence to these hopes.

However, right from the outset, I was one of the very few persons who doubted the capability of the Buhari-led government to fight corruption. My doubt was not because he is a toothless bull-dog, but was based one premonition: he personalised the fight against corruption, not institutionalising it.

Beyond just a mere premonition, I knew that fighting indiscipline under a military regime and fighting corruption in a democratic setting, was never going to be the same ball game. Government policies could be unilaterally implemented in a military regime, but requires structural interaction of institutions for such policies to be implemented in a democratic rule. And this is what I call inter-institutional complimentarity.

As systemic and endemic corruption has become in Nigeria, it has eaten deep into the socio-political and economic fabrics of the country. In fact, it has been systematically institutionalised. For this reason, any attempt to fight corruption must as well be institutionalised – institutions, not individuals must be empowered to tackle it.

However, right from the outset, I was one of the very few persons who doubted the capability of the Buhari-led government to fight corruption. My doubt was not because he is a toothless bull-dog, but was based one premonition: he personalised the fight against corruption, not institutionalising it.

Now, make no mistake about it: in any battle, the approach to the battle matters more than the battle itself. This, I am sure President Buhari should have known as a militarist. As Zhang Yu, in the classical book, the Art of War by Sun Tzu, succintly puts it: “A skillful martialist ruins plans, spoils relations, cut off supplies, or blocks the way, and hence can overcome people without fighting”.

Indeed, fighting corruption shouldn’t only be about probing and prosecuting people after they must have stolen our commonwealth, it should be about blocking the institutional loopholes that allows for all manner of illict financial flow; for when this is done, incessant setting up of probing panels may not be needed.

Sadly, however, the approach this government adopted in fighting corruption and the palpable reticence of President Buhari, has given birth to strongmen (cabal), who undermine institutions of the state. The late Chief of Staff to the President, Abba Kyari, probably epitomized the under-ground powers these strongmen wield within this government. Many political observers have even gone on to say that if Kyari were to be alive, the suspended EFCC Chairman would not have been removed.

Like many other African countries, the Nigeria state has deliberately built strong personalities at the expense of institutions. Weak institutions but powerful personalities (oligarchs), of course, is the effect of this deliberate action.

Within the circles of government, these oligarchs interfere excessively into the affairs of public institutions. They, however, allow the institutions, particularly the prosecutorial and law enforcement ones to function, but only to the extent that it goes against their perceived political enemies, or maybe cover their dirty tracks.

For one to understand how and why the personalization of our institutions breed corruption, impunity and gross inefficiency, it is imperative to first understand how the recruitment process of those that manage Nigerian institutions work. As sytem theorists would allude to, for the stability and continuity of any politcal system, one of the fundamental functions the system has to perform, is political recruitment.

If the above assertion is anything to go by, it means every dysfunctional political system would definetly recruit dysfunctional people to manage her institutions, and vice versa.

It is needless to say that the recruitment processes of the managers of Nigerian institutions are mostly based on nepotism and favouritism – all embellished with enthnic and religious sentiments. Appointments into sensitive government ministries, agencies, parastatals and commissions are made for the subtle reasons of political exigencies.

With much abhorrence for meritocracy, Nigerian politicians are known for appointing their cronies who could do their biddings into offices.

Even when the right and qualified persons are recruited to head ours institutions, they inadvertently personalize it to the detriment of the institution. The National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), for instance, and for the right reasons, was all about Late Prof. Dora Akunyili, that I now struggle to remember the names and achievements of other successive Director Generals after her. The same could be said of the National Orientation Agency (NOA) under Mike Omeri as DG.

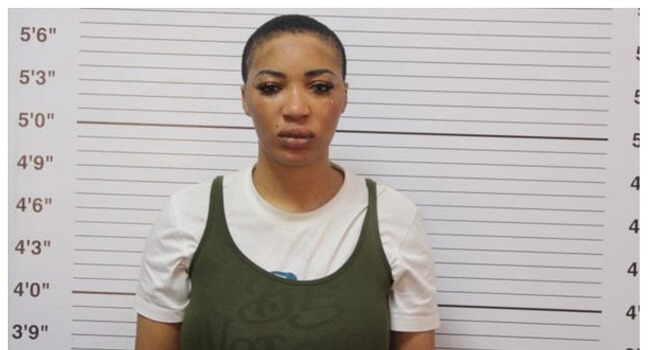

The appointment of Ibrahim Magu back in 2015 to head the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) crystallized the faulty recruitment process of Nigeria. The presidency had turned dearf ears to the weighty reports of Department of State Services (DSS) incriminating him. Twice was his name sent to the Senate for confirmation; and twice did Senate reject his nomination.

The insistence of the presidency, in any case, to have kept Magu on acting capacity as the head of EFCC for five years, meant that he was probably the only person who could do their bidding at that time. Because in a country of over 200 million population, it was inexplicable to know that he was the only person qualified to head the anti-graft agency.

As would be expected, the defiance of the presidency to retain Magu emboldened him. Just like a boy sent to steal by his father would break any door with his feet, Magu immediately swung into action, personalised EFCC and flagrantly disobeyed court orders – turning down the writs of habeas corpus of his detainees.

EFCC under Magu may have become a little bit effective, but their effectiveness served his interest and the interest of the powers that backed him. In every loot recovered from the corrupt members of the past administration, it was relooted by the sanctimonious cronies of the present administration.

If the prima-facie case established against the suspended EFCC Chairman is anything to go by, then the watchdog has eaten the bone hung on its neck: which obviously is a taboo in my village.

Though the travails of Magu has been reframed to mean that there is no sacred cow in this government. To me, however, it means that the fight against corruption is not yeilding any meaningful result.

With the ignomious removal of Magu and suspension of 12 Directors of EFCC; suspension of 2 Executive Directors and the Managing Director the Nigerian Social Insurance Trust Funds, and the embarassing halitosis of corruption exuding from the ongoing House of Representatives probing of NDDC, it means corruption is still percolating in this administration.

And for those who had hoped that corruption would be fought to a standstill by the Buhari-led government, I am sure that with the recent happenings, their hopes must have been dashed. Admittedly so, even the Vice President, Prof. Yemi Osibanjo knows that the fight against corruption will now get more difficult in Nigeria.

Speaking at the 20th anniversary programme organised by the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) on the 14th of July, 2020, the Vice President said: “The fight against corruption is nuanced and hydra-headed, it is not going to get easy; as a matter of fact, it will get more difficult by the day and many people will become discouraged in standing up against corruption”.

In all, if fighting corruption was a hill to climb, then personalisation of our institutions have further made it a mountain to climb.

Chimaobi Afiauwa writes from Abuja. Feedback: [email protected].